Making space

The art world demands that all artists pay their dues — but it can be doubly so for artists of colour

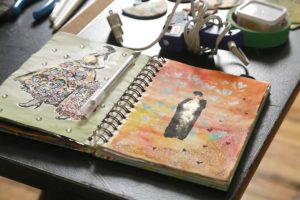

Photo: Amsa Yaro

THROUGHOUT HER CAREER as an artist in the Forest City, Amsa Yaro has spent a lot of it feeling somewhat isolated. Despite having settled in London a decade ago from Nigeria and having created art consistently for much of the last five years, Yaro is aware that she and other black artists are still working in a white art industry — an experience that can be isolating and creatively stifling, not to mention making it hard to earn a living from her work.

Click here to view article in magazine format

Her latest show, co-curated with Malvin Wright and themed The Future is Now, brings together more than a dozen black artists in town and is hanging in Somerville 630 in Old East Village. It was conceived as a celebration of black artists in the city, and to make their work more visible to audiences who might not otherwise see it.

“There are more of us all around,” she told the CBC, when the show launched. “More of us are coming along with our talents, with our different personalities and with different ideas.”

Despite a growing social awareness of black artists and a desire to see their work supported, artists like Yaro still face an uphill battle in accessing the kinds of resources and financial supports that many white artists often take for granted. Achieving sustainability in the arts is hard enough, but black artists often face even tougher conditions to make their business model work.

Story Continues Below

“It’s been very hard trying to break into the arts here,” Yaro says. “It’s a very close-knit community and it’s based on relationships. If you don’t know who’s who here, it’s not so easy to get your foot in the door.”

Things have started to improve, Yaro says. Social media, for one thing, has proven to be a powerful marketing and promotion tool for artists of colour, largely because it affords artists the ability to market and sell their art on their own terms, in their own voice and to their own communities — something that’s not always the case in galleries or by granting bodies, often eager to play up the diversity angle or only make overtures to diverse artists at specific times.

When it comes to commercial support for her work, “I don’t want it to only be during Black History Month or when there’s a protest,” says Yaro.

“It needs to fall on galleries, for example,” she continues. “They have to step up, and not just doing it because they want to tick the box of diversity. Nobody wants to be the token diverse person in any situation, even if we understand that sometimes that’s the one way you can open doors.”

There’s a raft of ways black artists could be supported, says Yaro. One way would be to boost arts funding across the board, which would also benefit established artists in other countries if the Canadian government made it a priority to support them finan-cially if they chose to relocate here, or to recognize international art credentials more widely.

Story Continues Below

It’s these areas, Yaro says, which may not seem at first glance directly connected to the business of making art, that are effectively making it harder for new artists to make a living.

Shows like The Future is Now reflect the other main way, though, that artists of colour can promote themselves: not having to worry about getting their foot in the door, but by creating their own door.

“If you can’t get into the in-group, what can you do to get yourself out there? You end up finding artists looking for all types of events.”

Yaro definitely feels change is possible and believes everyone will be better off for it if the ranks of working artists in the city were diversified. Asked how people can help level the playing field, her answer is simple.

“Buy more art from black people!” she says. “Open your horizons, experience any-thing other than what you already know. Variety is the spice of life.” ![]() Kieran Delamont

Kieran Delamont